The Brain Tumour Charity (BTC) has welcomed the NHS initiative to work to a 10 day turnaround to deliver the results of urgent cancer diagnostic tests to patients. This will ensure that those who need treatment will be able to access it sooner, and those who don’t will have their anxious waiting time reduced.

However, the BTC points out that a recent survey has shown that 15% of respondents said that their diagnosis took over six months from their first contact with a medical professional about symptoms. More concerningly, for 10% of respondents, their diagnosis took over a year.

To improve this unacceptable situation, the BTC calls for a Best Practice Timed Pathway for patients presenting with possible symptoms of brain tumours. Currently, there is no consistent approach as symptoms can be varied.

The outcome of initial medical appointments also varies between regions and if the patient presented at A&E, a GP surgery, or elsewhere. The BTC calls for the Non-Specific Symptoms pathway to be expanded to include the vaguer symptoms associated with brain tumours.

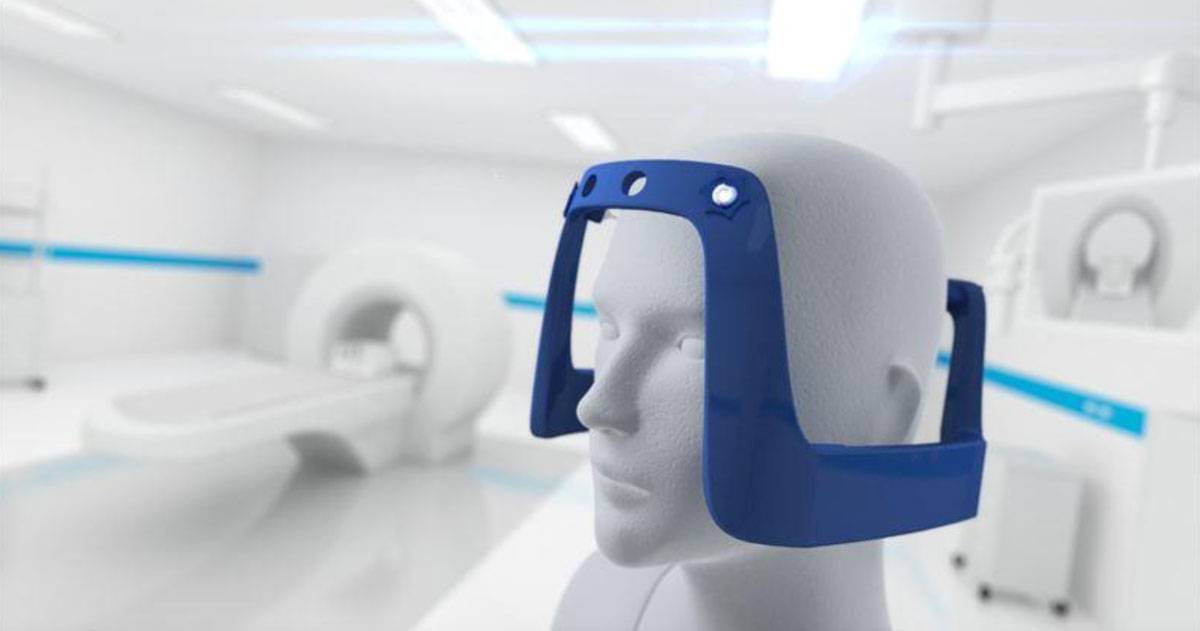

Furthermore, the BTC points out that many suspected brain tumour patients are sent to secondary care by GPs rather than for CT scans, ultrasounds, or brain MRIs. They call for universal direct access via GPs, and for extra investment in the workforce so that the resources are in place to offer more direct diagnostic services.

According to a recent NHS press release, record numbers of patients are now being checked for cancer, with 9 in 10 people with a positive diagnosis commencing treatment within one month.

Dame Cally Palmer, NHS National Director for Cancer, said: “It is a testament to the hard work of NHS staff that we are seeing and treating record numbers of patients for cancer, and have made significant progress bringing down the backlog and achieving the target for diagnosing three quarters of people within 28 days – all despite huge demand and pressures on the system.”

“Lives are saved when cancers are caught early and while we’re already diagnosing a higher proportion of cancers at an earlier stage than ever before – we want to ensure we’re making the absolute most of the diagnostic capacity in our community centres and hospitals.”

Minister Helen Whately said: “Catching cancer early saves lives which is why we’re prioritising early diagnosis and supporting the latest NHS drive to speed up the return of test results.”

“We have also opened 100 community diagnostic centres and these one-stop-shops have delivered over 3.6 million additional tests, checks and scans. We remain focused on fighting cancer through prevention, diagnosis and treatment backed up by vital funding and research.”

“We know there is more to do, and our ambition is to diagnose 75% of cancers at an early stage by 2028 which will help save tens of thousands of lives for longer.”

In adults, some of the main symptoms of a brain tumour include headaches, changes in vision, seizures, fatigue, nausea and dizziness, and loss of taste and smell.

If you would like some information about Gamma Knife surgery in the UK, please get in touch today.